“When I ask anybody where they’re from, I expect nowadays to be told an extremely long story,” once said the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who died February 10 at the age of 82.

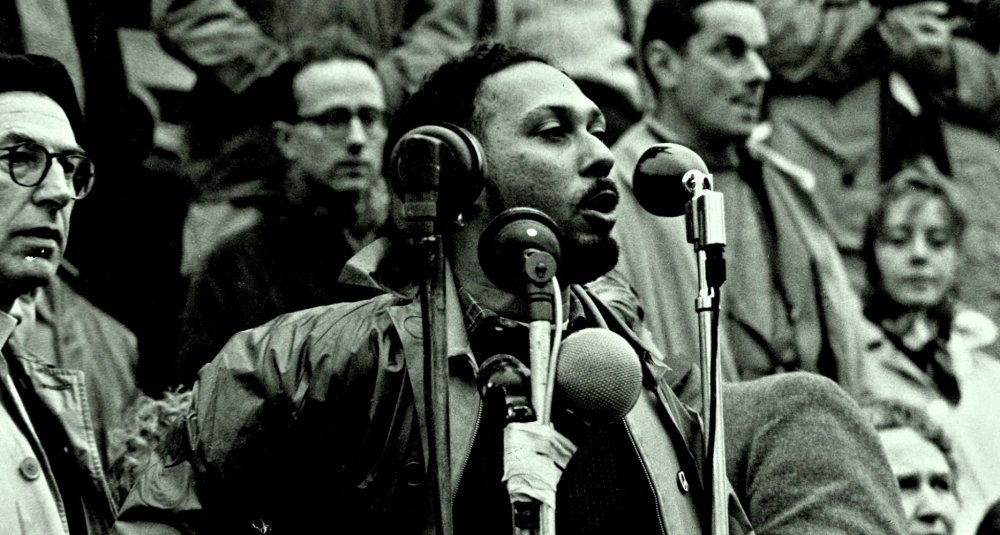

Hall was an English writer and theorist who co-founded the leftist cultural and political journal, New Left Review. He did this alongside such famed intellectuals as Richard Hoggart and Edward Thompson, but came from a much different background than his colleagues. Born to an aspiring family in Kingston, Jamaica, he arrived in Oxford in the 1950s among fellow members of the West Indian diaspora. He achieved an excellent education and felt respected by peers, but was also faced with racism due to the color of his skin. He began to see how matters of identity extended into all facets of life. In a community that was ever expanding due to mass media, he therefore felt it was necessary to address issues of culture and politics beyond an audience of students, professors, and intellectuals. He started appearing on television in the ’60s and became one of the first figures to pose complex questions about racism and identity to wide popular audiences. He asked questions that led to more questions, and therefore pushed viewers, families in their homes, to continuously wonder about how things become the way they are, and how common perspectives are reinforced in daily life. Additionally, Hall published his thoughts and questions in essays, lectures, and short films, thus becoming one of the most frequently cited cultural theorists to date.

In 2013, acclaimed English artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah made a documentary film about Stuart Hall called The Stuart Hall Project, which will screen in the Walker Cinema on February 19. It is a beautifully crafted chronological exploration of Hall’s life through archival footage and the sounds of Miles Davis, with which Hall resonated deeply. But despite its adherence to a logical linear progression, the film overwhelms its viewers with the impression of infinity. Cuts disappear as we hear the sound of ocean tides, and a lonely record keeps spinning on and on in an empty room. Akomfrah’s film is masterful in that it highlights a man’s unique devotion to truth — a way for which we yearn, but which seems forever out of reach. This is a quandary with which Hall’s life was so intimately tied that it seems he himself, in spite of his death, has become endless — a spirit of heated curiosity and investigation.

This film is the most direct and succinct way of learning about who Stuart Hall was as a person, how he achieved such notoriety as a man of thought, and what ideas flooded his life. Despite his immense complexity and the complexity of life which he embraced so fully, audiences will leave the theater feeling as if they had met the man himself. But Hall was a man who devoted his life to questions beyond himself. To honor him, simply keep on being curious.